Synopsis

Bubbles (Ball) and Judy (O’Hara) are the most important members of the dance company of Madame Lydia Basilova (Ouspenskaya). Bubbles attracts male attention with her sexy dances. In contrast, Judy favors the less showy ballet.

Jimmy Harris (Hayward), separated from his wife, meets Bubbles and Judy at the nightclub where the Basilova troupe is performing. Jimmy and Judy quicky become attracted to each other, making Bubbles jealous. The troupe’s tour is unsuccessful. Upon their return home, the sexy, uninhibited Bubbles finds work in a burlesque show, where the other members of the troupe are not wanted.

bnmjHoping to place the talented Judy in a ballet company, Madame Basilova takes her to meet ballet director Steve Adams (Bellamy). On their way to the ballet studio, Madame Basilova is fatally injured in a traffic accident. Without her teacher to introduce and recommend her to director Adams, Judy is unable to join the studio.

Lacking money but wanting to dance, Judy agrees to becomes Bubbles’ stooge in her burlesque act. The all-male audience cheers Bubbles’ rousing routine but boo, hiss, and make rude remarks during Judy’s refined ballet.

Steve has learned about Judy’s attempt to meet him and goes to see her in the burlesque show. He is impressed by Judy’s obvious skill and intends to talk with her.

Jimmy takes Judy to a nightclub where they meet his former wife and her new husband. Judy quickly realizes that Jimmy still loves his ex-wife. Later in the evening, Bubbles finds the drunken and confused Jimmy sitting on Judy's doorstep. She carries him off and marries him.

At the burlesque theater, Judy has tired of the male audience's abuse; she stops

her dance and lectures them about getting their fifty cents worth.

The

performers have to put up with the stares and

silly smirks their mothers would be ashamed of.

At home

they strut before their wives and sweethearts who see through them just the

same as we [the performers] do.

Steve, attending the performance with his assistant, starts clapping, and the

audience, shamed and impressed by Judy’s scolding, joins them in the applause.

In the dressing room, Judy accuses Bubbles of taking advantage of Jimmy. Their argument progresses into a hair-pulling, rolling-on-the-floor scuffle that ends with the arrival of the police and their arrest. At the night court, Judy is sentenced to 10 days in jail. Steve, who has learned about her arrest and come to the court, bails her out.

Sorry for her behavior, Bubbles makes up with Judy and frees Jimmy from the marriage. Jimmy reconciles with his wife who has separated from her second husband.

Judy goes to the dance studio to thank Steve. He promises to work with her and make her the ballet star that Madame Basilova knew she could be.

Discussion

The unusual plot centers on two determined and independent young women who seek careers in dance. Judy is a talented ballet dancer, an art form requiring refined skill and grace. Judy’s ambitions are blocked by the loss of her mentor and by her poverty. Bubbles has little skill as a refined dancer, but she is well built, attractive and dynamic. She displays these assets in her striptease performance to the appreciation of the male audience.

Judy and Bubbles are interested in men, but love and marriage are not the primary focuses of their ambitions. They are attracted to likeable, handsome Jimmie, but both easily give him up. Judy accepts his preference for his former wife, and Bubbles releases him from the drunken marriage. At the conclusion, there is a hint that Judy and Steve may develop a closer relationship than that of teacher and student.

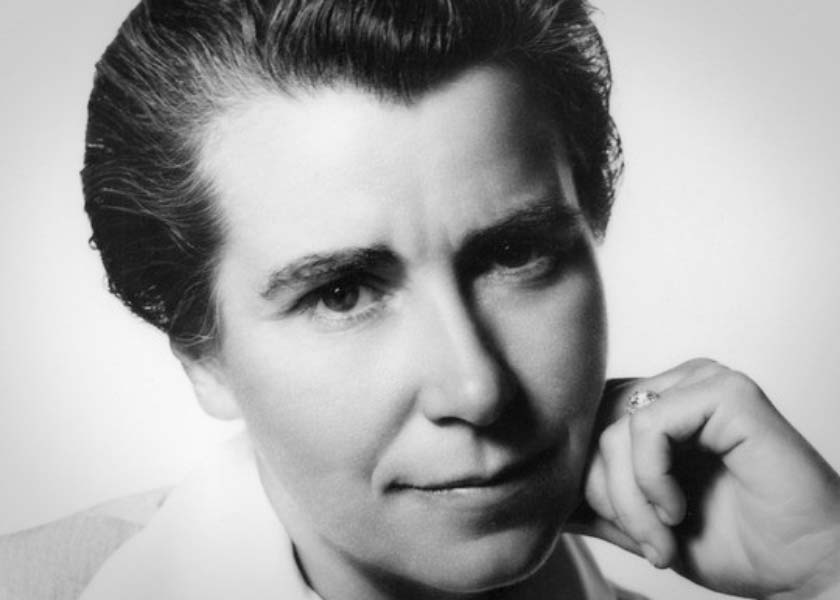

Lucille Ball excels as the flashy dancer, with a potent, but generally sympathetic, personality. Maureen O’Hara's character, although young and delicate, is equally forceful, if not as flashy. Louis Hayward provides a source of conflict between the women, leading to the bravura brawl. His relatively easy dismissal from their lives provides proof that these are independent women who can get on without a man.

Judy’s address to the burlesque audience is a demand that the men act properly to a woman. The men attending burlesque only want an erotic experience and a venue in which to make racy, suggestive and rude remarks to women. The women accept their money but do not respect them.

American burlesque shows were dominated by striptease, an erotic dance involving the removal of the dancer’s clothes in rhythm to music. A burlesque show would have up to six stripteasers, supported by one or two comics and a master of ceremonies. Although not exactly an art form and less physically graceful and demanding than ballet, striptease requires timing, body control, and a sensual deportment, in order to control the mood and make the performance sexy. The object is to titillate the male audience.

Producer Erich Pommer had signed a contract with RKO in November 1939 and planned his first film to star his young discovery, Maureen O’Hara. Roy Del Ruth was set to direct. Tess Slesinger and Frank Davis were writing the screenplay, and Eddie Ward, a prolific movie composer, was writing an original music score and modern ballet numbers.

Shooting began in April 1940; by May, Pommer and Del Ruth were disagreeing, mostly over Del Ruth’s interpretation of the script and his handling of Maureen O’Hara.

Del Ruth stepped down, and Dorothy Arzner was brought in to direct. Arzner had not directed a film since 1937 (The Bride Wore Red), but she was regarded as a woman’s director, and Pommer may have hoped for more cooperation with his ideas than he was getting from Del Ruth. Arzner (and presumably Pommer) rethought the script and started over, using less than one reel shot by Del Ruth.

The film premiered in August 1940 at the Golden Gate Theater in San Francisco,

with Arzner, O’Hara and Ball in attendance. A second opening was held in St.

Louis, and to promote the film, O’Hara and Ball made an extensive three week

personal appearance tour, visiting 15 cities. The change of directors and

reshooting of the footage had increased the cost. Despite an ad campaign and the

expansive personal appearance tour by the stars,

Dance, Girl, Dance did not attract many patrons and lost a

substantial amount of money for RKO. The Variety headline

'Dance' Floppo, $6000 in Cincy

was typical of attendence.

The films of Dorothy Arzner, the only major female director in Hollywood during the 1930s, center around the female stars, including Claudette Colbert, Ruth Chatterton, Joan Crawford, Katherine Hepburn and Rosalind Russell. Arzner began as a film editor and writer in the early 1920s, and directed her first film, Fashions for Women, in 1927. For her first talkie, The Wild Party (1929), she directed Clara Bow in her talkie debut. While at Paramount where B. P, Schulberg, her friend and strong supporter, was head of the West Coast studios, Arzner worked continually and directed nine films from 1927 to 1932. After she left Paramount, the intervals between directing assignments became increasingly longer, up to three years between each of her final three pictures. Dance, Girl, Dance is Arzner’s penultimate film; she made a war-themed picture, First Comes Courage, starring Merle Oberon in 1943, then retired from film direction. In the 1950s, she directed many commercials for Pepsi-Cola. Joan Crawford, wife of the PepsiCo chairman, helped get her the work.

Producer Erich Pommer (1889-1966) was beginning his second period in Hollywood. During the 1920s, Pommer was an important producer in Germany with Universum Film (UFA) and had produced many outstanding films for the studio, including Variety (1925), Faust (1926) and Metropolis (1927). In 1927, Pommer briefly left UFA after disagreements with the governing board and moved to Hollywood where he was the producer on several high quality films, including Barbed Wire (1927), starring Pola Negri, and Mockery (1927), starring Lon Chaney. He was planning further films at MGM when UFA hired him back. Pommer remained in Germany until the rise of Hitler. In 1933, he moved to England and subsequently partnered with Charles Laughton in a production company, Mayflower Pictures Corporation. Pommer and Laughton co-produced, and Laughton starred in, three films: The Beachcomber (1938), Sidewalks of London (1938), and Jamaica Inn (1939). Jamaica Inn, directed by Alfred Hitchcock, co-starred Robert Newton and Maureen O’Hara, a newcomer to films and Pommer’s discovery and protégé.

In 1939, with the war in Europe intensifying, Pommer, Laughton and O’Hara relocated to Hollywood. RKO took over rights to Mayflower Productions, and Pommer became a producer for the studio. Dance, Girl, Dance was his first film for RKO and the introduction of O’Hara to American audiences. Pommer released his second film, They Knew What They Wanted, starring Charles Laughton and Carol Lombard, in October 1940. He was preparing several other projects, including at least one for Maureen O’Hara, when he suffered a heart attack in April 1941 and had to curtail his activities. After the war, Pommer was commissioned by the State Department to supervise the German film industry. He produced several films in Germany during the early 1950s. Illness forced his retirement in 1955.

In 2002, Dance, Girl, Dance was listed as one of The Society of Film

Critics 100 Essential Films. In her discussion of the film, critic and author

Carrie Rickey points out that the feminists of the 1970s found a foremother in

Dorothy Arzner, and describes Dance, Girl, Dance as a subversive and

unconventional film directed from the heroine’s point of view. Rickey describes

Arzner as

often exploring the conflicted roles of women in contemporary society. In

Dance, Girl, Dance, two women pursue life in show business from

opposite ends of the spectrum: burlesque and ballet. The film is a meditation on

the disparity between art and commerce,

and confronts the standard Hollywood point of view of men leering at the women on

screen, looking at them in a way that their wives won’t permit.

In 2007, Dance, Girl, Dance, deemed

culturally, historically or aesthetically significant,

was added to the

Library of Congress, National Film Preservation, Film Registry and earmarked for

preservation as a work of enduring importance to the culture. The Brief Descrption

in the Registry quotes the 2002 article written by Carrie Rickey for The Society

of Film Critics.

Further Reading